Blog

Creative Urban Methods: Gluing

Corelia Baibarac-Duignan

In 2019 we launched the research initiative CRUM. Short for Creative Urban Methods, CRUM aims to develop a transdisciplinary toolkit of interdisciplinary methods for mapping and analyzing (issues around) infrastructures within public space to contribute to the development of (more) sustainable urban infrastructures. The toolkit is intended to be implemented in academic research and teaching contexts, as well as in contexts of participatory citymaking practices. CRUM wants to bring together ongoing urban and creative research in the social and geo sciences, and the humanities at Utrecht University. We aim to organize a productive exchange around this shared interest in (and perceived need for) a robust methodology for collaborative work. In a series of workshops already existing creative methods developed in various contexts within Utrecht University and beyond will be selected, fine-tuned and adapted for implementation in the context of research into (futures for) sustainable urban infrastructures. Outcomes of these workshops provide input for a book proposal for the toolkit and a didactic plan for its implementation in educational contexts at Utrecht University.

How might citizens be involved in transforming local data into forms of value that they consider beneficial for the sustainability of their neighbourhood? This question guided our project, “Co-Designing Local Data Interfaces: A Citizen-Engaged Co-Design Walkshop”, supported by Utrecht University’s Public Engagement Seed Fund. The start of the project coincided with the outbreak of the COVID-19 global pandemic, which helped us re-conceptualise creative urban methods as a matter of ‘gluing’.

There has been a surge in critical studies on the ongoing datafication of urban life (for example, in relation to data extraction, algorithmic processing and data-driven decision-making). This is because, usually, the data that are collected, the purposes for which they are used, and the forms of value into which they are converted, are beyond the grasp and access of ordinary city inhabitants. However, we felt that more needed to be done to re-contextualise these discussions by reaching out and engaging citizens with the abstract notion of ‘data’ through creative and imaginative ways.

We focused our project in Leidsche Rijn, a relatively recent and fast-growing ‘Vinex’ neighbourhood of Utrecht, developed in a formerly thriving agricultural area. In order to reach out to residents, we decided to connect with an artist collective (The Outsiders) who are active in the area. The artists have gained extensive knowledge of the neighbourhood and established relationships with local communities over time, engaging them through artistic interventions that reflect local issues. Thus, in addition to accessing local residents through their mediation, we consider this strategy to be important for linking discussions around ‘data’ with issues that people consider important.

Moreover, working within a co-production framework, we find it important to develop our methodology together with our collaborators. This also means connecting with their on-going projects and events so that we can define common goals and contribute to each other’s work. One such opportunity was to link with The Travelling Farm Museum of Forgotten Skills, a long-term co-initiative of the artists and CASCO Art Institute to generate an art-ecological practice in Leidsche Rijn.

At the beginning of our collaboration, we had planned to develop a series of workshops in the neighbourhood. However, this also coincided with the coronavirus outbreak, which meant that we had to reconsider our approach, and decided to combine digital and analogue forms of engaging with the neighbourhood.

Digital engagement: a ‘hotglued’ site

As a way to continue to engage the residents at a time of social distancing, we creatively adopted technologies of communication and other digital tools ‘at hand’, or commonly used in everyday life. We did this by setting up a website as a starting point for conversations about the neighbourhood through the lens of food, an essential part of everyday life even (and felt more acutely) at times of crises.

Reflecting datafication processes, which typically involve the production, transformation and use of data to inform future interventions, we focused the website on food production (growing), transformation (cooking) and imagined futures (neighbourhood food stories). The website was created as a ‘digital depot’ to reflect the artists’ physical depot and workshop space located in the neighbourhood (an empty shop space in a new shopping mall). Through its online presence, the website has the potential to invite contributions beyond a specific moment in time, which typically is the case of a physical workshop.

Inspired by a previous project (Baibarac et al., 2019), the website combines existing platforms and technologies brought together – or ‘glued’ – using Hotglue, a visual website-making tool that does not require coding skills. By re-using and re-appropriating what already exists, Hotglue allows the creation of modular and agile toolkits, open to experimentation, tinkering and replacement. Moreover, when used as part of digital methodologies, this approach supports co-design processes. Neither the artists nor us are coders, yet we used Hotglue as a canvas for exchanging, negotiating and prototyping ideas quickly and productively, even when working at a distance (all of us worked remotely when developing the website due to the lockdown restrictions).

Analogue engagement: a ‘data’ walk-shop

Nevertheless, in September 2020, more relaxed coronavirus-related rules allowed us to organise a small-scale workshop, entitled Sowing Sustainable Prospects: Explore the Landscape of Leidsche Rijn and Imagine the Future. As suggested by its title, the main aim of the workshop was to enhance residents’ awareness of their everyday environments and, together, start to imagine alternative neighbourhood futures. We developed the method in collaboration with the artists to reflect our initial research question on civic participation in the datafied city, while addressing their interest in sustainability and building on ideas that emerged during the co-design of the website. The method included three steps:

The first was a ‘data’ walk – with a difference. Rather than looking for data understood in a technological sense (which is typically the case in ethnographic critical data studies) we invited the participants, organised in small groups, to openly explore the landscape of the neighbourhood. We proposed the themes of sustainability, nature and food, and asked them to take (instant) photos and collect any fragments of the landscape that made them think about these themes (e.g., objects, elements from nature, stories from people they met).

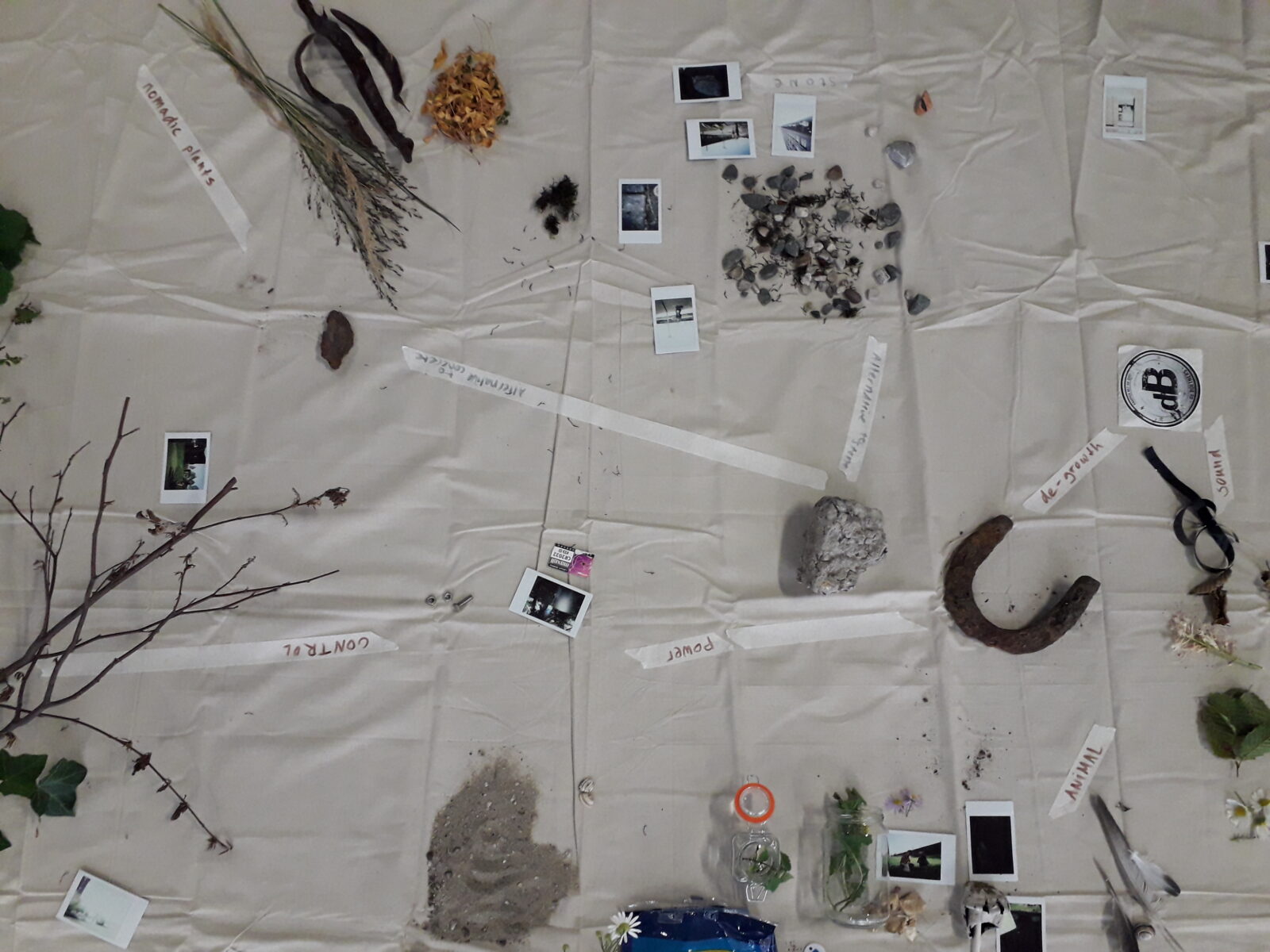

The second step involved mapping the ‘data’ collected. Each group placed their data collections onto a large tablecloth, on the floor of the depot. After presenting their collections and walk reflections, the participants were invited to link the data by making associations between the various items and grouping them into themes. The relationships between the items had to be marked with tape, annotated with a brief explanation. At the end of the mapping, a constellation was formed, involving the data (objects, photos) and links between them (tape).

The third step was aimed at engaging the participants in imagining other (sustainable) futures for the neighbourhood, based on the data collected, the group discussion and the constellation created in the previous step. To creatively make the transition from awareness (the here and now) to speculation (imagined futures), we first used a short artistic video, which projected the participants into an a-temporal, post-pandemic, future. This was followed by the task to write a ‘postcard from the future’, using visual material from the constellation to create it. They were asked to relate the postcard to a theme from the constellation, connect it to a location or place of interest encountered on their walk, and write it from the perspective of an object or element from the environment in a future time. The postcards, taken together as fragments of alternative neighbourhood futures, were exhibited in the window of the depot where the workshop took place. To enable further contributions from residents, a QR code was placed onto the window, linking to the futures section of the digital depot (future stories).

‘Gluing’ creative urban methods in times of global pandemics

Besides supporting the co-design of the digital engagement methodology (the website) at a distance, Hotglue also provided us with the metaphor of ‘glue’, which opens up possibilities for re-conceptualising ‘creative urban methods’.

Used as a verb, and closest to its definition, ‘gluing’ can be seen as an active and creative process of connecting different elements, such as materials, objects and tools. In our case, this is visible in the co-creation of the data constellation during the workshop, and in the use of different analogue and digital tools as part of the engagement methods we developed.

Nevertheless, gluing is also a matter of fostering relationships, which can lead to creative crossings (Verhoeff and Dresscher, 2020), for instance between academic and artistic knowledges and practices, as illustrated by our collaboration with The Outsiders. In turn, this can enable the emergence of new understandings and creative approaches that would have not taken place otherwise (the digital engagement and the workshop methods are illustrative examples). At the same time, such relationships can anchor abstract topics (e.g., ‘datafication’) in a particular urban context, bringing them closer to people’s everyday environments and lived realities, while retaining connections to broader societal issues, such as sustainability and climate change.

Last but not least, gluing is also about relating methods and their emergence to specific moments in time and situations. In our case, the COVID-19 pandemic has directly shaped our methodology, particularly through the need to creatively respond to social distancing restrictions. However, rather than ‘locking’ our response to the present, it has opened up opportunities for reflecting on the future, through our methods and also conceptually. For example, using the future stories section of the website, residents can start to think about, imagine and formulate alternative futures for their neighbourhood. Moreover, asking the workshop participants to write postcards from the future and from a non-human perspective (e.g., objects collected) challenged them to imagine and reflect on futures of coexistence.

Through the workshop, particularly, we have seen how speculation and imagination can give room to multiple perspectives and voices, while exposing diverse values, worries and aspirations about what otherwise could remain abstract notions. In this sense, although our methods emerged in response to a specific moment in time, they have enabled us to reflect on the importance of engaging people with future imaginaries. Shaping new social imaginaries departing from the here and now (and memories of the past) might be one step forward in the process of assembling new practices so that other futures can actually come about.

Reflecting on our experimental process, the metaphor of glue(ing) suggests that ‘creative urban methods’ are not a given, or something that one can simply take out from a toolbox and un-discerningly use. This does not mean rejecting what are more traditionally understood as ‘creative methods’, such as those from a design tradition, but acknowledging that the ‘urban’, by its nature, presents a need for “ongoingness and process, not sequence and goal attainment” (Halprin and Burns, 1974, p.26). Indeed, creative urban methods, particularly when addressing participation and collaboration in the city, often emerge as an organic response to a context, a situation, and a moment in time; in our case, datafication in the context of a neighbourhood, the lockdown, and a global flu pandemic. Furthermore, they can help shape concepts, here gluing, which can provide an ethical framework for how we think about, assemble and use our creative urban methods: What are we responding to and why? How are we going about this? And who or what may benefit or lose out in the process?

References

Baibarac C, Petrescu D and Langley P (2019) Prototyping open digital tools for urban commoning. CoDesign: 1–18. DOI: 10.1080/15710882.2019.1580297.

Halprin L and Burns J (1974) Taking Part: A Workshop Approach to Collective Creativity. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Verhoeff N and Dresscher P (2020) XR: Crossing and Interfering Artistic Media Spaces. In: Hjorth L, de Souza e Silva A, and Lanson K (eds) The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media Art. London: Routledge, pp. 482–492.